First to speak was USUI Hidekazu, chairman of the Nuclear Energy Systems Steering Committee of the Japan Electrical Manufacturers’ Association (JEMA) and a director of Toshiba Energy Systems & Solutions Corporation, who presented the environment surrounding Japan’s nuclear industry from the viewpoint of a plant manufacturer, revealing many problems. He also introduced requests from the industry to the national government and activities by the industry toward achieving carbon neutrality by 2050.

Outline of Usui’s presentation:

Assuming that all existing nuclear power plants (NPPs) in Japan are to be operated for 60 years, the country’s nuclear installed capacity would fall substantially in 2040 and thereafter. Although the goal of a nuclear share of 22% in 2030 is achievable, it will be essential to construct new NPPs to realize carbon neutrality by 2050. Building NPPs is a long-term project that must be started now.

Meanwhile, the nuclear industry in Japan is confronted with various issues, the first of which is the maintenance of supply chains. Lifecycles in the nuclear power business are long, and it is necessary for different types of businesses and companies to participate at each stage. At present, the technological areas and supply chains to be maintained are unbalanced, in light of the current situation wherein the industry is engaged in work on safety measures under the new regulatory standards, or otherwise involved in restarting plants. Consequently, orders for characteristic nuclear technology have been disrupted at many firms, along with the maintenance of human resources and production lines, and the companies themselves are considering withdrawing from their nuclear businesses altogether. In order for the companies essential to the nuclear industry to be able to continue those businesses, it is thus absolutely essential that NPPs be restarted as swiftly as possible and that prospects for the construction of new plants be clearly shown.

Ensuring a broad range of technology and human resources is an issue for nuclear vendors, too. Responding to the decommissioning of the Fukushima Daiichi and the restart of existing plants has caused imbalances in the technology area as well, resulting in difficulties in securing the human resources necessary to build new NPPs. In addition, those experienced in new plant construction are getting older and retiring. Meanwhile, as for college students interested in the nuclear industry, not only their numbers but also the distribution of their majors is an issue. Since the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, the number of students expressing interest in a possible nuclear career has remained steady, while those among them majoring in mechanical and electrical subjects have substantially decreased. Students majoring in electrical and mechanical subjects have many career options, and are not particularly attracted to an industry that offers “no attractiveness.”

Another issue is a loss of facilities and opportunities supporting research and development. In circumstances where the future of nuclear businesses is unclear, it is difficult to maintain large research and other facilities in the private sector. Those facilities are not only used for research, but also play an important role as venues to educate young researchers through practical training. Along with international cooperation, including the utilization of irradiation test reactors overseas, domestic infrastructure must be improved and developed for the sake of human resources in Japan and the competitiveness of domestic technologies.

Nuclear power is a carbon-free power source in practical use and a proven technology contributing to decarbonization. Toward the achievement of carbon neutrality by 2050, I want the national government to come out in support of the construction of new and replacement reactors. Specific plans for new and replacement reactors at power companies can be made once that national policy is clarified. Substantive activities to maintain and improve technological power would also be possible at nuclear vendors and in supply chains. Students would be motivated to enter the nuclear industry, thereby enhancing the human resources required to further improve safety and technological development.

In addition, I want the national government to promote the development of fast reactors toward completion of the nuclear fuel cycle. That would enable the plutonium in spent fuel to be utilized, and potentially reduce toxicity as well, leading to solutions to nuclear back-end issues. Ultimately, moreover, public understanding of the entire process would be enhanced. The development of fast reactors would also provide students, young engineers and technicians with places to tackle innovative development with enthusiasm. Nowadays, private-sector companies are barely investing in long-term development, including fast reactors. I want the government to show leadership in establishing a framework connecting industry, government, and academia, and in improving and developing research infrastructure.

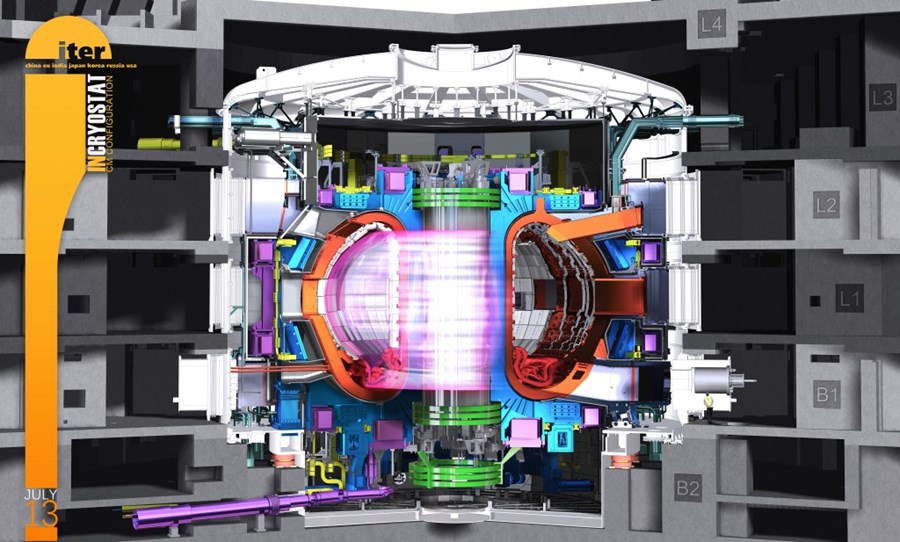

The domestic nuclear industry is making various efforts toward the achievement of carbon neutrality by 2050. A next-generation LWR is being developed, offering the world’s highest levels of safety and economy, to coexist with renewable energy. Small LWRs have been actively developed recently, both domestically and overseas. Such smaller reactor systems can be simplified, reducing the initial costs of construction. A high-temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGR) is expected to contribute to decarbonization in the industrial area, including hydrogen generation, in addition to providing electric power.

Those advanced reactors represent long-term projects, from development to practical implementation. I hope to make the domestic nuclear industry attractive through cooperation among industry, government, and academia under a clear nuclear policy by the national government.

In order for nuclear power to be broadly accepted by the public, nothing is more important than safety and the accumulation of a record of safe operation at restarted plants, based on the lessons learned from the accident at Fukushima Daiichi. The industry wants to maintain and improve industrial infrastructure that supports quality in the maintenance of operating plants in various ways. Improving, maintaining and strengthening the foundations for advanced technology—which will not only support nuclear safety and safe operations, but can also respond to future societal needs—are major obligations of the nuclear industry, including nuclear vendors and members of supply chains. Under longstanding, clear policies of the national government on such matters as the restart of NPPs and their long-term operation, along with policies for new and replacement reactors and advanced reactor development, the nuclear industry will make sincere efforts toward the acceptance of NPPs by society and their effective utilization.

+ +

Next to speak was Director George BOROVAS, a partner and head of the nuclear practice section in the Tokyo office of Hunton Andrews Kurth, who examined the financial aspects of new nuclear projects, offering thoughts on financial risks related to the raising of funds.

Outline of Borovas’s presentation:

Financing is very important to any nuclear project. When addressing financing, risks must be considered. Factors in financial risks include historical and current experience with project delays and cost overruns, power market uncertainties, the need for long-term human resource development, significant financing amounts and long development and construction periods, and nuclear liability. In risk analyses, reputational risks must be considered, too. Those are negative social perceptions associated with nuclear, political risks and public acceptance issues, image and safety concerns post-Fukushima, nuclear nonproliferation, and nuclear back-end issues. Those reputational risks may cause project delays and cost overruns, which everyone wants to avoid.

I am often asked to explain the nuclear finance model, but, as of 2022, there is no singular one. The primary ones are anchored around the Export Credit Agency (ECA) and vendor financing, but there is no standard model. There is no multinational support, such as from the World Bank.

When it comes to nuclear project financing, the first thing to do is minimize the risk. For that, it is necessary to ensure the safety of the project, ensure supply chains, select an experienced vendor, and manage the project through owner-vendor cooperation. Also relevant are the capacity and capability of the regulator, support systems by the government, and long-term human resource development, among others.

What is important to investors in a project is not technology. Investors are interested in certainty of revenue generation, clarity on the role of government, responsiveness of the regulatory regime, reputational concerns, project management risks, and market risks. Financial support from the government is imperative in order to assure investors. Nuclear is not subject to traditional project financing, and government funding and support are essential.

A question I hear often from other industries is, “If nuclear energy is the answer, why does it need governmental support?” Simple. The benefits of nuclear energy—energy security, mitigation of climate change, industrial development, enhancement of education levels, promotion of R&D, and more—are benefits to society. Its costs and benefits cannot be analyzed as they would be in conventional project financing. Societal benefits should enjoy the support of society.

Pure reliance on government funding, however, can lead to loss of fiscal discipline, lack of accountability, and inefficiency. Government funding and support should be seen as a bridge to private sector support. Speaking to investors should be in their language, rather than the language of engineers. Boasting of “cutting-edge” technology sounds to investors like first-of-a-kind (FOAK) risk. When “consortium” is emphasized, investors think only of internal disputes.

SMRs are the most exciting subject in the nuclear industry today. There are many benefits, but FOAK risk is unavoidable. Regulatory structures are untested. Accordingly, financing may not be easy. Looking at it on a long-term basis, however, they certainly present a unique first-mover opportunity.

+ +

The next panellist, Chris HEFFER, director of Nuclear Power and Decommissioning in the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) of the UK, described that nation’s civil nuclear policy. He showed great eagerness for Japan and the UK to work together to ensure energy security and achieve net-zero emissions.

Outline of Heffer’s presentation:

The 55th JAIF Annual Conference is being held at an important time for the world. The ongoing tragedy in Ukraine and rising fossil fuel prices globally reveal the need for energy independence and safety. From the aspects of both decarbonization and energy security, swift shifts to clean energy are essential for Japan and the UK. The UK sees nuclear energy as a key means to that end. Currently, it is focused on promoting both large nuclear reactors and SMRs as new projects. There exists a long history of nuclear cooperation between the UK and Japan. We want to work on issues common to our two countries, including energy security and achievement of net-zero emissions.

Over the past years, the UK’s nuclear policies have undergone exciting evolution. Both the “10 Point Plan” and the Energy White Paper produced by the government of Prime Minister Boris JOHNSON emphasize the government’s goal of promoting nuclear power as a clean energy source. To support development of large and smaller nuclear reactors, funding of up to EUR525 million is committed. The government entered negotiations on the Sizewell C NPPs, has allocated EUR170 million, and is committed to reaching a final investment decision (FID) on at least one singular nuclear power project during the current Parliament.

In October 2021, the Nuclear Energy Financing Bill was introduced in Parliament to enable use of a regulated asset base (RAB) model for new NPP projects next year. The government also announced a Future Nuclear Enabling Fund of EUR120 million to provide support for businesses entering the nuclear field in the future. During the second half of the current fiscal year, a nuclear roadmap will be published, which will focus on the large and advanced nuclear reactors that the UK will need in the future.

The Ukraine situation affects the UK’s energy security strategy.

In 2016, the government decided to support the Hinkley Point C (HPC) NPPs, where two EPR units are to be operated. HPC is important to both the regional and national economies, eventually creating over 25,000 new jobs. Operation of the first unit will be in June 2026. When HPC is completed, it will provide electricity to 6 million homes, about twice the entirety of London. This will be the key to the UK’s achieving its net-zero goal toward 2050. In the Energy White Paper, the government commits to reaching a final investment decision (FID) on at least one 1,000-MW class NPP before the end of the current Parliament.

Sizewell C would produce 3.2GW of electricity, enough to power around six million homes and reduce CO2 emissions by about 9 million tons annually. The government expects negotiations with the developer to conclude in the spring of 2023.

In 2016, the government concluded a contract for differences (CfD) for HPC. In light of the situation at that time, it was appropriate financing. Under the CfD contract, consumers bear no costs until a power plant begins generating. However, cost effectiveness may be improved later when the RAB model is shown to be valid for large-scale singular asset projects and the technical expertise accumulated through recent project construction is applied.

The Nuclear Energy Financing Bill enables use of the RAB model for new nuclear projects and serves as an incentive for a company to promote a new project in an effective manner within the scope of RAB. The RAB model allows an investor to share part of the project’s construction risk with consumers. Under this model, payments by consumers can be applied to project expenses during construction and all risks are shared by consumers, investors and the company, by which financing costs may be lowered. Consequently, electricity charges may be reduced.

Safe decommissioning and clean-up of all civil UK nuclear sites is a national priority. The UK has a plan for secure, cost-effective clean-up and decommissioning and is capable of safely managing and disposing of all waste. The significance of the task is reflected in the annual budget of around EUR3 billion of the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA). The UK has managed radioactive waste generated from NPPs and other sectors for several decades. Approximately 94% of waste is low-radioactive and is treated safely at existing facilities. The rest—high-level radioactive waste—is stored safely and securely at facilities around the UK and is to be finally disposed of at the UK’s planned geological disposal facility (GDF). In England and Wales, investigations are being carried out on candidate sites suitable for the GDF. Four sites are currently under consideration in the selection process.

In order to develop innovative nuclear technology, including SMRs and a GDF, it is important that the nation recognize the role of nuclear energy. Hosting COP26, the UK took on a large challenge in regard to recognition by the people of nuclear energy. Although only 38% of the British people supported nuclear energy in March 2021, nuclear was a major presence at COP26. For two weeks, many interesting, attractive events were staged. Diverse voices of young people talking about nuclear energy also stimulated many positive discussions.

+ +

Moderator ENDO Noriko made the final presentation in Session 2 under the title of “Nuclear Energy and Energy Security.” She outlined the situation for Japan and world, and identified various issues.

Outline of Endo’s presentation:

The world has been turned upside down by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In Japan, through the process of full deregulation of the retail power market, electricity generation and transmission have been separated, and the power supply and demand balance has become tight. The assault on Ukraine then occurred and procurement of gas and oil from Russia has been severely impacted. While the occurrence is primarily in Europe, Japan within the global market has been greatly affected. Burning coal has been viewed negatively in European countries, but now coal has become necessary. As for natural gas, rather than raw natural gas via pipeline, procurement is now of LNG. This, too, is going to affect Japan, the world’s #2 LNG procuring country.

The Japanese government, i.e., Prime Minister Kishida, at a plenary session of the House of Representatives on April 12, finally mentioned that “all energy sources, including nuclear, are necessary.” The government has tended to avoid anything related to nuclear when an election is coming. There is nothing referring to replacement reactors in the Strategic Energy Plan revised last year.

Whether nuclear businesses can be sustainable hinges on whether they can contribute to energy security or not. As electrification and digitalization proceed, the time is coming when demand for electric power will be overwhelmingly high. Japan’s target for power-source composition in 2030 is a nuclear share of 20-22%, which might not be realized. And if nuclear power is required in 2050 and thereafter, it goes without saying that replacement reactors are necessary. Is that possible or not? When older reactors are replaced, what kind of business entity will be doing it? And replaced with what kind of reactor? Matters such as political support, including funding—even the possibility of continued existence as private businesses—will have to be considered as well.

Decommissioning is an issue common to all nuclear operators. It is necessary to consider whether it should be done by them individually, or in cooperation.

There is also the matter of global market development. No new reactors will be built in Japan in the 2030s. Japan will have to think about whether it will be able to contribute to the overseas market as a member of the Western bloc.

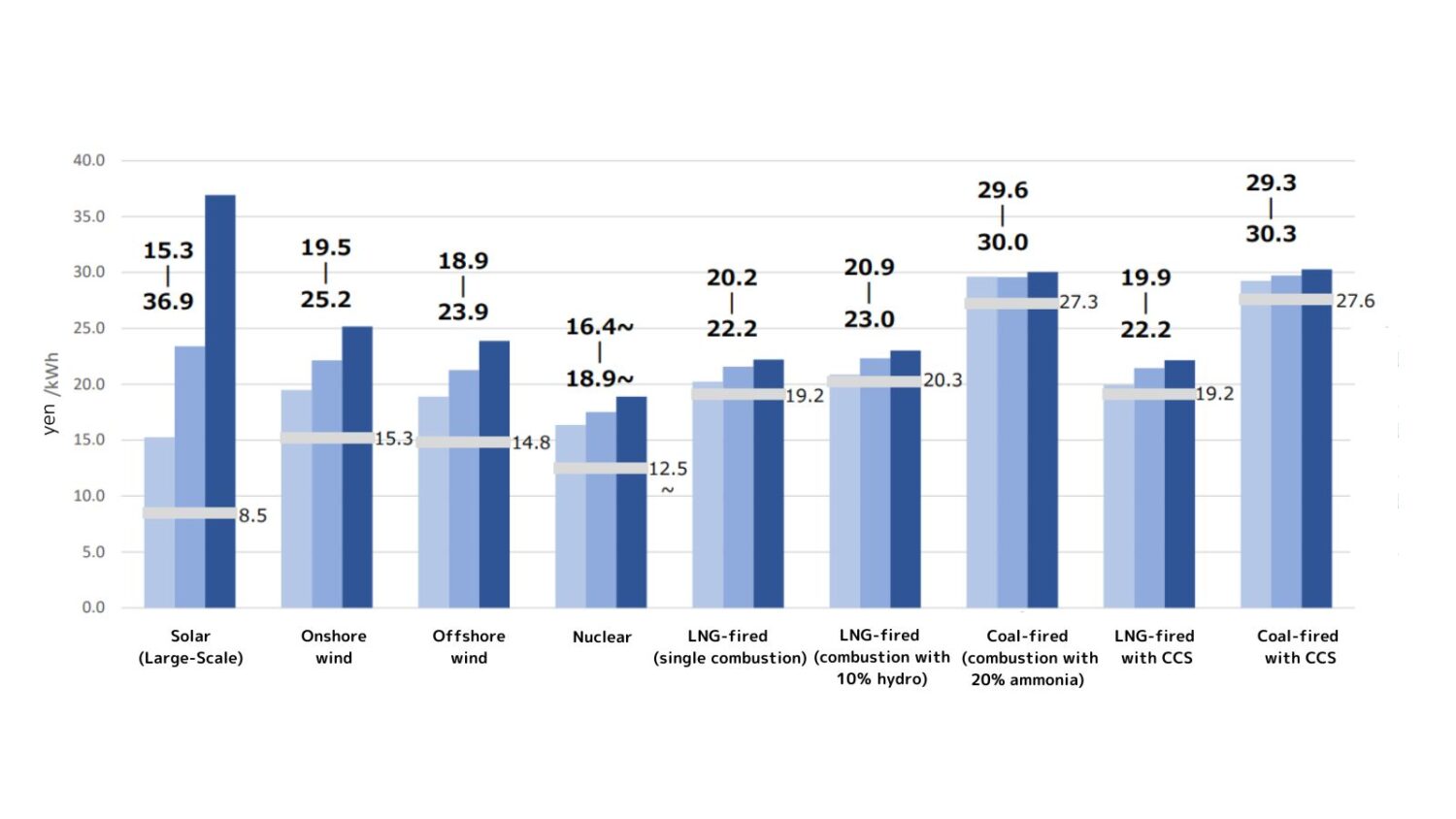

In Japan, nuclear power, as a base-load power source, does not contribute to power shortages. This is a structural problem as a result of deregulation of the power market. In 2009, prior to the great earthquake of 2011, the nuclear share was 31%. In 2021, it was only 3%, barely included among base-load sources. The current state is that while Japan chants about carbon neutrality and green energy, it burns coal, and LNG is the base-load power source.

Another problem is the delay in restarting NPPs. When the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) was established, it was expected to take only 5 months or so for a safety examination. The first unit examined by the NRA under the new regulatory standards was Sendai-3, and approval took 767 days from the filing of the application. Times for examinations then steadily got longer—as long as 5 years recently. The procurement of resources depends on imports, and Japan’s loss of earnings is as much as JPY4.7 trillion. It has been calculated that, if carbon prices were added, the amount would be JPY11 trillion.

Globally, the building of new nuclear reactors is mostly limited to Russian and Chinese reactor types. This is a concern in regard to nuclear proliferation, and yet reactor designs of Western countries are hardly employed. A nuclear project spans 80 years from launch through decommissioning. The Chinese government provides funds for a reactor project and buries the counterpart country in debt. Relationships between China and counterpart countries are fixed, which causes concerns. The U.S. and UK are focusing on SMRs. One reason may be to force a shift away from the Chinese and Russian business models.

+ +

Panel Discussion

Panel Discussion

Endo: Japan lost the ability to regulate rate-of-return as part of deregulating the retail power market, but can learn much from the UK’s RAB model: how nuclear projects can be financed, and how “foreseeability” can be achieved and maintained.

Heffer: The UK has just begun applying the RAB model. At HPC, the CfD model was used for financing. Consumers share cost overruns caused by FOAK risks. HPC can be said to be a national project of France and China, rather than a UK project. In pursuit of better means to distribute risks among consumers and a developer, the RAB model emerged. It has been used for construction projects, including construction of expressways and tunnels. With the RAB model, the means for distributing risks has changed. Each government individually invests in a project. The UK likes trying various political models.

Endo: I understand that, in response to strike prices becoming too high with CfDs, the main purpose of the RAB model was to fix prices as rate-of-return regulation did, and to maintain stable costs. Is it possible to gain understanding of users and consumers on bearing financial burdens from the stage of construction?

Borovas: It is very important for Japan to look at the UK’s experience. The UK has used these models for many years and has also studied them. When developing these models, there are many things to learn in the development process itself.

Neither the UK nor the Japanese government wants to bear any construction risks at all. They let private companies construct power plants. Once the plants are supplying electricity, the government will buy it at a guaranteed price. In such a situation, the developer has to bear large risks at the initial stage. Still, two things are needed to carry out the project. A guarantee that the government backs the project, and a high price built in and an allowance for the risk.

The RAB model is basically a UK project for the UK people. It is not realistic to expect one party to take all the risk. Risk sharing is necessary, which eventually leads to savings. This is the point on which understanding of the people may be difficult unless it is adequately explained. Florida in the United States provides an example of a failure to do that. There are many elderly people there whose belief remains that they should not bear the burden for the future. But the Ukraine crisis is creating an environment in which matters of energy security and the like can be productively discussed.

Endo: As a result of the Ukraine crisis, energy security is emerging as a societal issue. There is also the matter of carbon neutrality. Control by the public sector is coming to exceed that of the private sector. What is the proper responsibility of the government for national nuclear policy?

Usui: If the government clearly shows its support for investment in long-term R&D, industry will be able to make specific plans. Ultimately, human resources are critical, and they cannot be produced—educated, developed—on demand. The nuclear industry has to become an industry that attracts them.

Borovas: In addition, the issue must be addressed through a public-private partnership (PPP) model. That is basic infrastructure. Everyone should recognize it as the foundation of the economy. There is no choice but for the public and private sectors to work together.

Heffer: I also think that a government should engage in nuclear development. In the UK, there is yet little involvement by the public sector. But financial risks may increasingly be taken by the public.

Endo: Why are advanced nuclear reactors so trendy?

Borovas: Certainly, advanced reactors and SMRs now have momentum. Construction times are short and they are quite safe. The ultimate purpose of nuclear projects is to supply electric power. Engineers are eager to improve their own skills. They have to actively manage in order to ultimately connect to the grid. Unless they enable the plants to generate electricity, their technology means nothing. And you should remember the risk that advanced reactors may not fit within existing regulatory systems.

Endo: I have heard that in the United States, costs can be reduced in cooperation with regulators. In Japan, it was reported that Japanese developers have invested in NuScale, but, domestically, there are voices saying construction of small reactors in Japan is not realistic.

Usui: The advantages of SMRs are short construction times, low cost and good safety, but what would be the case in Japan? Without speaking too generally, Japan’s power supply grid is large, and sites where such reactors could be located are limited. As a rule, small reactors are less economic than large ones. Although initial costs are low, the question is whether small reactors should be chosen over large ones when siting locations are limited. We must consider what is really most economical. Preferring SMRs from the beginning is not an adequate approach.

Heffer: Engineers are excited about advanced reactors because those reactors embody their dreams. The question is how fast the designs can progress. SMRs have advantages, but also have drawbacks inherent in a nuclear project, including nuclear security and back-end issues. Personally, I think SMRs and large reactors will end up with similar costs. However, as the project scale is smaller, the effect of failure would be smaller. In this area, international cooperation is very important. If the SMR market becomes global, costs and risks could be shared. Economic efficiency will change in the future. As for now: Get local consent and build one! The contribution to the local economy cannot be denied.

Endo: What about high-temperature reactors? I think it is certainly more efficient than carrying hydrogen from a distant area.

Endo: What about high-temperature reactors? I think it is certainly more efficient than carrying hydrogen from a distant area.

Usui: It is good to have various options. This can make the industry more attractive. One of them is high-temperature gas-cooled reactors. Hydrogen production and thermal supply to the industry can be expected. In Japan, energy consumption by industry is great. Not only high-temperature reactors: SMRs are part of dreams, too. I hope many people will get involved in their development and that the industry will be revitalized.

Endo: When we think of future supply chains, cooperation among Western countries will be important to compete with China and Russia, won’t it?

Borovas: Yes, exactly. The catchphrase of the Chinese/Russian model is “The government bears all the burdens.” One-stop shopping is attractive. But it is not realistic. One-stop shopping does not work. Western countries can stand up to them. But no private-sector company alone can handle the risks of project delay and cost overruns. Government needs to manage them. The environment will have to be improved so that private-sector companies can compete internationally with the Chinese/Russian model.

Endo: Saying “the government decides its policy” is the same as saying “societal consent is obtained.” But is it really possible to ask the people to bear the burden of maintaining nuclear as a business?

Borovas: Looking around the world, local communities hosting NPPs support nuclear energy. They have enough information and recognize the benefits of it. It is important to advertise those benefits. Yes, it is important to talk about safety, but I think there is too much talking only about safety. Safety comes first, but the meaningful aim, the objective, is safe power generation. No airline promotes its services with the theory of why planes can fly. People like Tesla because it is inspiring and exciting and attractive—cool. This is how people feel.

Endo: Would there be any advantage to nationalizing nuclear power? Disadvantage?

Borovas: Maybe at the stage of building the first unit; thereafter, efficiency suffers. I think the private side should take the risks from the fourth or fifth units. It is good to use the same technology repeatedly. It may not be exciting, but continuing to use the same technology (building a series of the same model) enables the private sector to continue forward with nuclear projects.

Usui: It might be effective if the government took the risk. Construction of the same reactor model might also be useful.

Heffer: Yes, although not exciting, continuing the same reactor model is effective. The UK government is ready to take many risks, but I think competition in the private sector plays a greater role.

-1.png)