In a panel session on September 7, the second day of the Forum, four panelists, including ISHII Noriyuki, editor-in-chief of the Atomic Industrial Journal (JAIF’s owned media), discussed space development and public understanding, particularly as it relates to the use of nuclear energy in space.

The Forum—launched in 2002 to broadly share information and spur interest inside and outside the industry in the state of and prospects for space development—was meeting for the 22nd time. This was the first time that the assembly treated the theme of nuclear use in space.

Prior to the discussions, YAMAGUCHI Yukino—a sophomore at International Christian University (ICU), who was the planner of the panel and served as moderator—talked about the aim of the gathering.

Saying that people often react reflexively against the use of nuclear energy on account of the negative images associated with nuclear power and energy, she raised the question of how to present the subject to the public in a way that promotes the understanding of new technology.

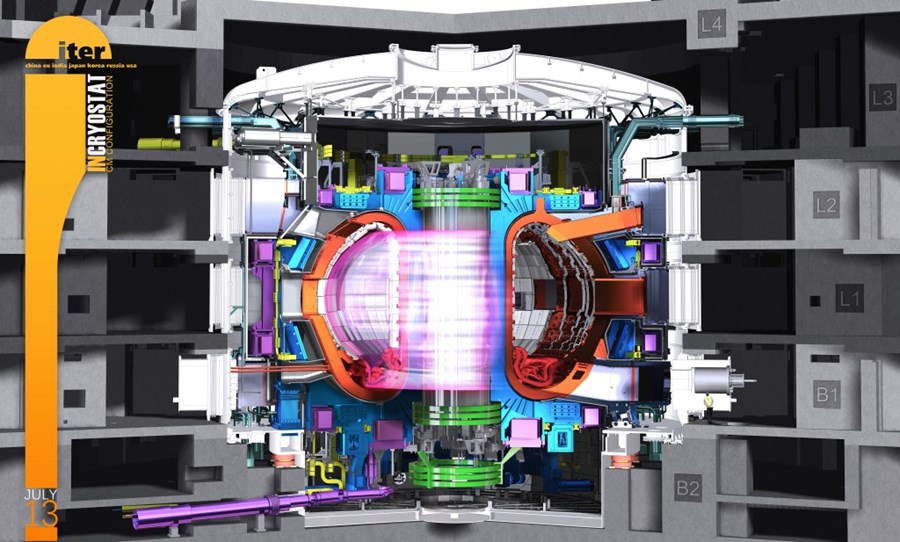

The United States, ahead of other nations, pioneered the use of nuclear energy in space. For example, three nuclear batteries were installed in the space probe Voyager 1, launched in 1977.

However, Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) only recently included the topic of developing element technology for nuclear batteries as a Space Strategy Fund Project in April 2024. Concerning that, Professor TAKAKI Naoyuki of the Department of Nuclear Safety Engineering at Tokyo City University pointed out that the MEXT funding referred to the nuclear batteries as “semi-permanent power source systems,” showing that even national projects tend to avoid using the term “nuclear.”

At the session, JAIF’s Ishii said, “Just like the space engineers of today, nuclear engineers once shared a dream for the future.” He noted that space exploration from now on may also not obtain society’s understanding, citing the examples of unfounded fears concerning “Akitakomachi R”—a kind of rice created with irradiation technology and misunderstandings about food additives.

Ishii then stated that the lack of scientific literacy was the biggest obstacle in obtaining public understanding on new science and technology.

A quest for “zero risk,” Ishii said, was also a societal distortion, adding that people need a proper understanding of being “safe,” which is objective, and feeling “secure,” which is subjective. Something can be objectively safe and yet people can feel insecure about it.

He emphasized that people must have a proper sense that if something is safe, they should feel secure, and went on to say that a society should not be allowed where a sense of “being safe but not feeling secure” has currency.

Asked what is needed to promote public understanding on unknown and future technologies, Ishii argued that everyone—across all lines of industries—must work to raise scientific literacy across the board. Otherwise, he said, referring to Niemöller’s “First they came” confession, “When the public comes for the space industry, there may be no one to speak out on its behalf.”

He called on the participating students “to routinely ‘extend your antennas,’ that is, to pay attention to areas other than space, and then . . . actively speak out.”

-1.png)