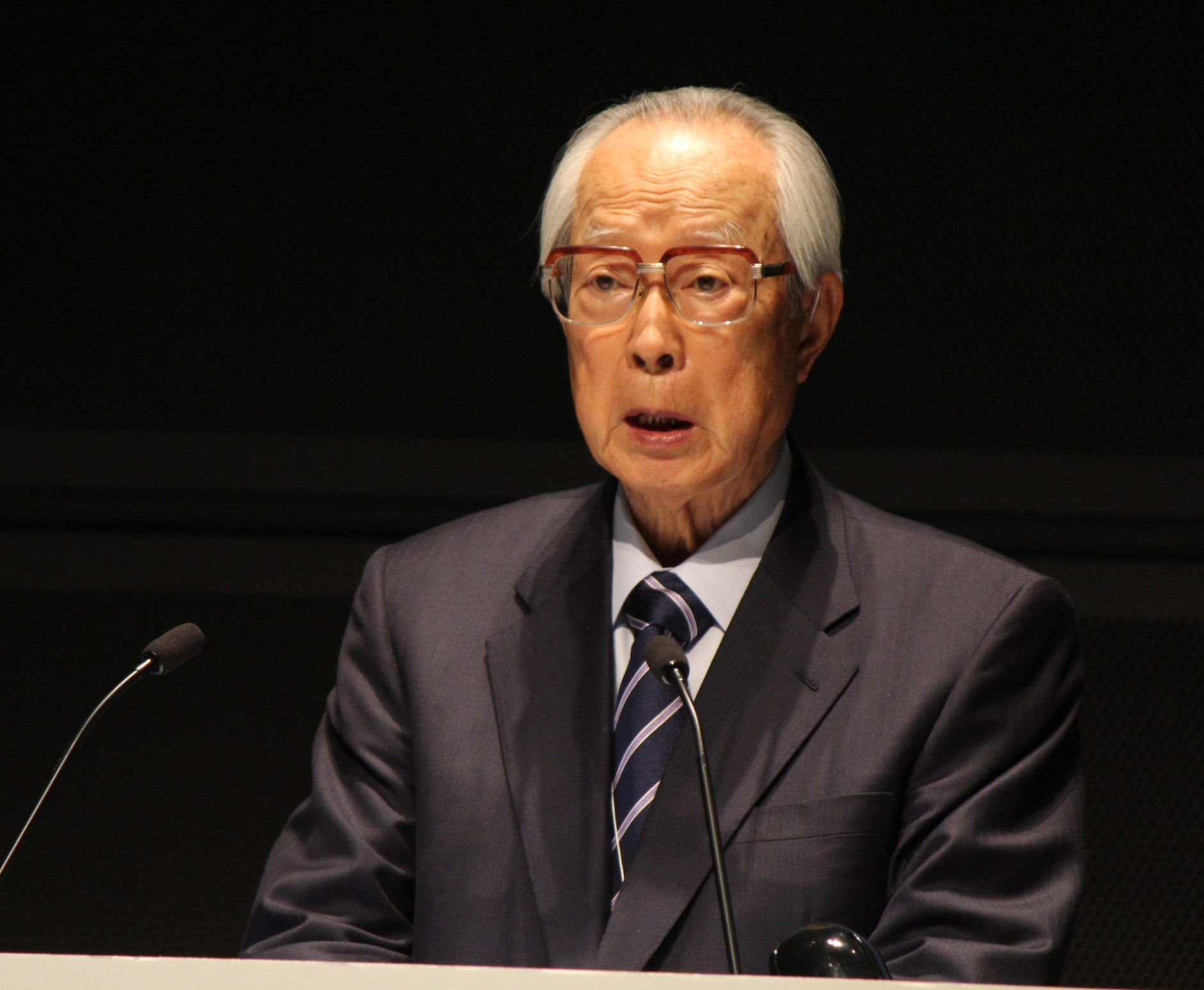

“Do you understand the difference between science and technology?” That was the question posed to me by Jiro Kondo, former chairman of the Science Council of Japan, and one of country’s top scientists, when I interviewed him about the December 1995 accident at the fast-breeder reactor (FBR) Monju (280MWe) in Tsuruga City, Fukui Prefecture, in which sodium leaked from the coolants used in the reactor.

On March 28, 2015, at the age of 98, Kondo died of old age at a hospital in Tokyo. The words he left us from the above episode not only demonstrate his character, but also remind us how important it is to think about the basics of science, and upon reflection, the essence of all things.

The FBR Monju is a nuclear reactor aimed at pursuing the engineering ideal of converting the uranium fuel in reactors into a new fuel, plutonium, using fast-speed neutrons, then extracting energy from that plutonium through nuclear fission. The accident at Monju involved the leakage of 640kg of sodium on account of the breakage of a thermometer inserted into the secondary cooling system, causing a fire in the reactor building. As the shape of the narrow cylinder of the thermometer’s sensor casing was such that sympathetic vibrations were produced easily, the sodium flowing at 40cm/sec within a stainless tube—measuring approximately 1cm across—created repeated vibrations that in turn caused metal fatigue, with the liquid sodium flowing out through that tube. The cause of the accident was thus a design mistake.

When asked about the accident, Kondo responded plainly, “Oh, it’s (caused by) an irresistible force.” Without thinking, I asked him, “Irresistible force?” That was when he replied by posing me the question cited in the title of this article.

As I had majored in chemistry in college, I thought I had reflected somewhat on the difference between science and engineering already, but even so, Kondo’s explanation was splendid. “Let’s think about launching a rocket. If it shaped like this, with this amount of mass, and is launched at a certain angle and acceleration, it ought to fly along a trajectory accordingly. Up to this point, demonstrating those things is the job of science, using equations, right? But do you really think that the rocket will fly if made precisely according to the demonstrated principles? No, it will definitely fail. In such a case, you fix this and change the design on that, so as to try to find out the source of the problem. After repeated trial and error, the rocket finally takes off. That is the job of engineering. That’s why there is no such thing as failure-free technological development. Experiencing hit-and-miss situations is inevitable.

That was the background to his reference to an “irresistible force.”

He then continued talking: “Fast breeder reactors can extract energy over an extremely long period using just a small amount of uranium fuel. In a certain sense, it is the ideal nuclear reactor. However, it also has inherent risks, and is not easy to develop. Even France, which had enthusiastically pushed the technology, gave it up halfway, and before it realized it, Japan found itself at the frontier of the development of this technology worldwide. Looking back on it, has there been any technology that Japan has built from scratch? Japan has been clever at taking what the West has developed after a long struggle, then brushing it up and producing superior products. Still, there is really nothing that Japan has created on its own. But now, Japan is engaged in creating this new technology. Will Japan succeed in this challenge then? Or will it give up on it just because of a single sodium leakage accident?”

He then continued talking: “Fast breeder reactors can extract energy over an extremely long period using just a small amount of uranium fuel. In a certain sense, it is the ideal nuclear reactor. However, it also has inherent risks, and is not easy to develop. Even France, which had enthusiastically pushed the technology, gave it up halfway, and before it realized it, Japan found itself at the frontier of the development of this technology worldwide. Looking back on it, has there been any technology that Japan has built from scratch? Japan has been clever at taking what the West has developed after a long struggle, then brushing it up and producing superior products. Still, there is really nothing that Japan has created on its own. But now, Japan is engaged in creating this new technology. Will Japan succeed in this challenge then? Or will it give up on it just because of a single sodium leakage accident?”

Even such a slow-witted person as I could not fail to sense the philosophy embedded in his question. In addition, a renewed perusal of his personal history made me realize what he had built up in his career. After majoring in mathematics at Kyoto University, he entered the engineering faculty at the University of Tokyo, this time majoring in aeronautical engineering. His life itself thus really was one that joined the worlds of science and engineering.

After the giant earthquake that struck eastern Japan in March 2011, and the subsequent accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plants of the Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO), there were fewer opportunities to hear such philosophizing musings from scientists and technologists. Or perhaps it might be more apt to say that few scientists make the kind of message anymore that strikes the hearts of a lot of people.

As a result of the Fukushima Daiichi accident, much attention has been directed toward the problem of the disposal of high-level radioactive waste (HLW), and Kondo left an important legacy in the resolution of that problem as well.

Ever since Japan’s nuclear administration first started generating electricity in 1963, it put off the problem of how to dispose of HLW, or “pretended not to know about it.” The event that put an end to that way of thinking and addressed the problem in a public arena was the establishment of the Special Committee on Disposal of High-Level Radioactive Waste by the Japan Atomic Energy Commission. Tateo Arimoto, who was the section chief on waste policy of the Science and Technology Agency at the time, and now professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS), persuaded Kondo, then the chairman of the Central Environmental Council, to chair the special committee as it was launched.

Kondo said, “This is a problem that we cannot run away from. We must discuss it in a way that is visible to the Japanese people, and come up with the wisdom that will lead to its resolution.” Under his initiative, the problem of HLW disposal finally reached the eyes of citizens.

At the time, some people in governmental environmental agencies and environmental groups were confused and upset, saying, “Why should the chairman of the Central Environmental Council, a major figure in environmental problems, dirty his hands with nuclear energy?” In response, Kondo said, “Nuclear energy and the environment are not antithetical. It is the duty of scientists to transcend disciplinary boundaries and demonstrate a proper course of action.” His words reflected the basic starting point of communication, which is to transcend narrow disciplinary boundaries and present citizens with multiple assessments and values—in other words, to be interdisciplinary, which is the goal of modern science communication.

In retrospect, what is the current state of progress in the development of FBRs, which Kondo depicted as a challenge of technological creativity?

Since the sodium leakage accident, the Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation (PNC), now the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA), which was in charge of Monju’s development, ended up escalating the accident into an “incident” by covering up the existence of videotapes recording the accident as it happened, as well as making repeated announcements of falsified information, and even suffering from people within the organization committing suicide. Thereafter, the reactor finally was able to reach the point where operation could be resumed, but owing to the repeated occurrence of troubles, operation has not restarted even now in 2015, some 20 years after the accident. Similar to the confusion arising after the Fukushima accident, the problem can be identified as being not so much one of the technology itself but rather the so-called human aspects surrounding it.

Meanwhile, the world has steadily continued to address the challenge of FBRs.

Since 2012, India has been operating the same type of FBR (500MWe) as Monju. In April 2015, Chairman S.A. Bhardwaj of the Indian Nuclear Society spoke at the Annual Conference of the Japan Atomic Industrial Forum, Inc. (JAIF), saying, “We have learned much from the data gained from Monju’s development process and operation, and have applied it in our development.”

Also, there were 27 occurrences of sodium leakage at Russia’s Beloyarsky-3 (BN600, FBR, 600MWe) from the time it started generating electricity in 1980 to 1995. Kiril Komarov, First Deputy CEO of ROSATOM, who also participated in the same Conference, said there, “We made successive improvements to the reactor on the basis of our experience with the accidents, allowing us to significantly upgrade the safety of the FBR.” Last year, Russia reached the first criticality of an even larger fast reactor Beloyarsky-4 (BN800, FBR, 864MWe).

Jiro Kondo: “Failures are part and parcel of technology. What’s important is what one learns from the failures.”

I wonder how much Japanese public opinion, the country’s nuclear energy administration, as well as the Diet legislators who represent the policy decision-makers, have really acquired the logical reasoning represented by Kondo’s quote.

Kondo, whose hobby was swimming, was active in a broad variety of fields, including his major fields of study, aeronautical engineering (having been involved in the basic design of Japan’s first passenger aircraft since World War II, the YS-11) and mathematics, as well as the field of pollution, climate change, the environment, and nuclear energy. When did he cultivate such an interest and ability in so many fields?

Kondo, whose hobby was swimming, was active in a broad variety of fields, including his major fields of study, aeronautical engineering (having been involved in the basic design of Japan’s first passenger aircraft since World War II, the YS-11) and mathematics, as well as the field of pollution, climate change, the environment, and nuclear energy. When did he cultivate such an interest and ability in so many fields?

According to his oldest daughter, Ryoko Watanabe (now 67), “I think it was due to his personal history. My father had to interrupt his studies during World War II to participate in military service. After the war, he returned to university, but the field of aeronautical engineering was closed off during the Occupation, so he was unable to pursue his research all the way straight through. Instead came to learn those other things naturally.” It is said that Kondo had worked in a variety of workplaces to earn a living, including other educational institutions, as well as the Institute of Statistical Mathematics. There was a period when was taught at the University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo, when one of his students was the now-Empress Michiko.

In front of Kondo’s memorial tablet after his death were words of condolence written by the Emperor and Empress.

Brief Biography

Born in Shiga Prefecture. Served as professor at the University of Tokyo. Served as chairman of the Science Council of Japan between 1985 and 1994, and vice chairman of JAIF between 1994 and 2000. Received the Order of Culture in 2002. Served successively as the head of the National Institute for Environmental Studies, chairman of the Japan Prize Foundation, among others.

Shigeyuki Koide

Shigeyuki Koide

Born in Tokyo in 1951. Chairman of Japanese Association of Science & Technology Journalists, director of JAIF, and Visiting Scholar at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS). Formerly head of the science section of Yomiuri Shimbun and researcher at the Science Communication Unit of the Imperial College London.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article originally appeared (in Japanese) in the May 2015 issue of the JST Science Portal column