Born in 1957 in Osaka, Sawa graduated from Hitotsubashi University with a degree in economics in 1981, and joined the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI, now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, or METI). In 1987, he obtained a master’s degree in public administration from Princeton University.

Sawa served as manager of the Environmental Policy Division of METI’s Industrial Science and Technology Policy and Environment Bureau, as well as the policy manager of the Natural Resources and Fuel Department of the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (ANRE), among other positions.

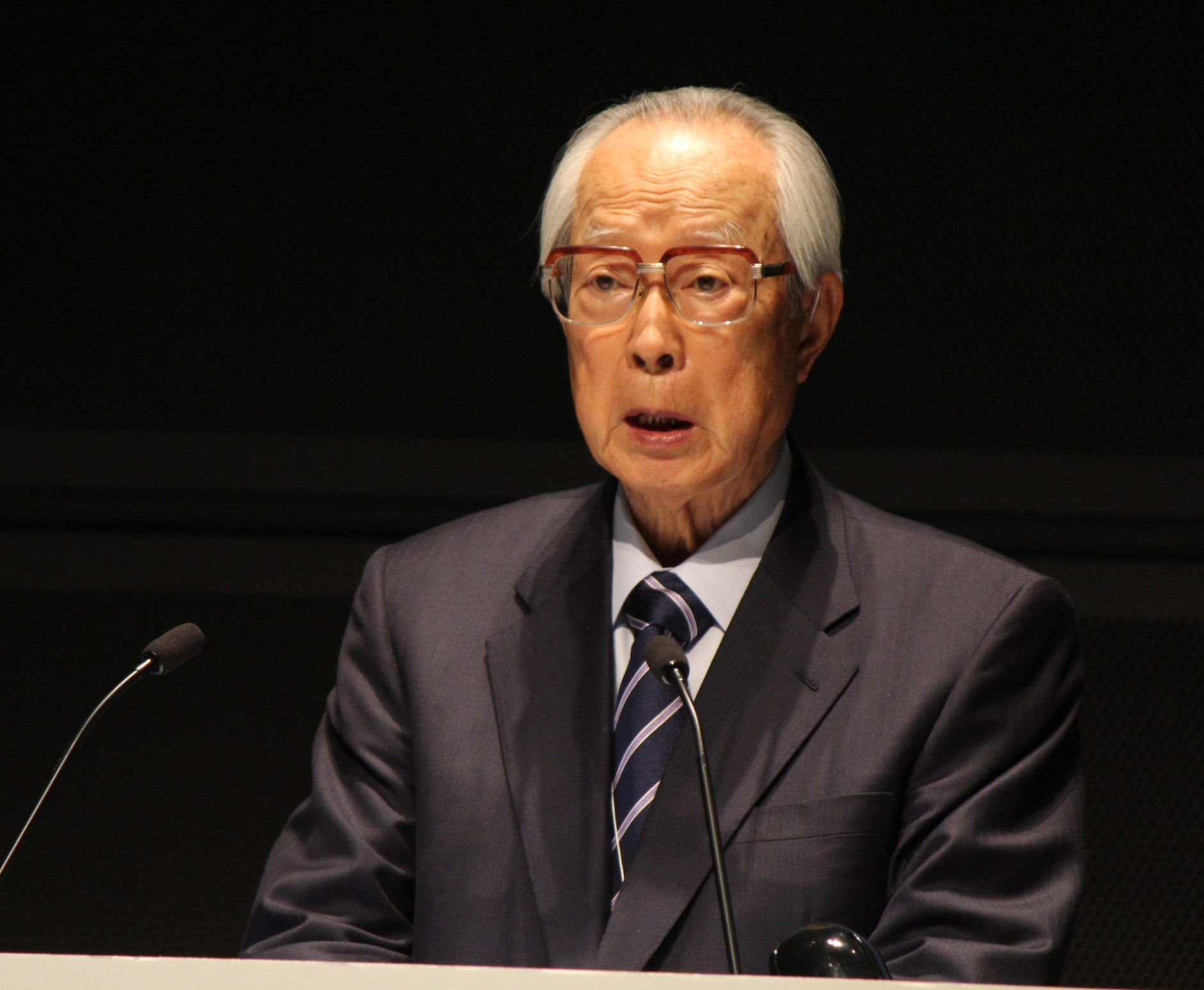

From 2004 to 2008, he was a professor at the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Tokyo. Starting in May 2007, he served as executive senior fellow of the 21st Century Public Policy Institute, a Keidanren think-tank. After the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plants in March 2011, Sawa spoke frequently at symposiums sponsored by the institute, offering thoughtful, constructive opinions toward rebuilding Japan’s energy policy.

In 2014, Sawa appeared as an unsworn witness before the Diet’s special commission on nuclear issues, testifying on the question of restarting the country’s NPPs, a matter now in the spotlight nationally. He said that NPPs should be understood as “economic property,” and that regulation should be rational in an engineering sense. He also argued that the aim should be to operate NPPs safely rather than simply eliminate them.

Sawa had a close relationship with the Japan Atomic Industrial Forum (JAIF). He appeared at JAIF’s annual conferences in 2014 and 2015. He also gave lectures at forums of JAIF members on the ideal form of nuclear safety regulation and other topics. Our memories are fresh of April 14, 2015, the second day of last year’s annual conference, when, coincidentally, the Fukui District Court issued a temporary injunction against the Kansai Electric Power Co., Inc. (Kansai EP) prohibiting the restart of the Takahama-3 and -4 NPPs. Sawa then spoke knowledgeably of the high risks when nuclear power was sued, and the challenges ahead involving Japan’s judicial system.

He left us too early, and there has been an outpouring of sadness.

Among his various achievements and writings, those on nuclear regulatory administration and compensation for nuclear damage are particularly well known. He never felt bound by bureaucracy or technicality, and often took part in women’s energy-related forums. He listened carefully to the opinions of people and incorporated them into his own work.

Below we offer two of the many messages we have received, both from women. We hope that they will help you understand Sawa’s strong will to rebuild Japan’s energy policy and his personally friendly character.

Kanna Kozu, writer

“Wish We Could Chat over a Cup of Tea”

Akihiro Sawa once took me and a few others to a special Chinese restaurant. One of the dishes served was a plate with a bird’s tongue. He taught me how to eat it—telling me to hold the soft bones on both ends and shave the meat off with my teeth. Everyone at the table began eating, and I nearly shouted, “I never had a deep kiss with a bird before!”

Breaking into a broad smile, he said, “I never expected Kozu-san to say such a thing.” I said, “But I do! I don’t talk only about energy and nuclear power.”

He said that he and his wife once had an argument over shampoo ingredients, and that they took an overseas trip to overcome their grief at the death of their dog. He also told me that they were so busy searching the Internet to find their next stray dog that they ended up hardly enjoying the scenery of the country. In short, he told a lot of stories that had nothing to do with energy and nuclear power.

When Sawa and his wife went to Spain to watch soccer, he sent me an e-mail, saying, “Your brother lives in Madrid, doesn’t he? We met a person who knows him.” When I wrote that I liked the jazz pianist Michel Camilo, he wrote back saying, “I do, too. Whenever he performs here, I go with a friend. Next time I will invite you.”

Upon an invitation from him to buy sample products from Misawa, his apparel company, several members of the Women’s Energy Network (WEN), including Noriko Kimoto, Etsuko Akiba, Wako Tojima, Kiyoe Asada and Yuki Aomi, went numerous times. After that, we enjoyed eating and drinking along with Sawa and young men employees of his company.

In a time of hardship, we were of the same generation, working together in the world of energy. There was one year’s difference between Sawa and me. Most of the time we spent together, we talked seriously about work. When I asked about the Nuclear Damage Compensation Law, he explained to me thoroughly about it on board the train on the way to a symposium. When we visited sites in Fukushima and Kashiwazaki, he always spoke in a way that raised the morale of those working at the sites.

I wish we could have gone to a Michel Camilo concert together with him. I wish we could talk more about shampoo and dogs and apparel. I wish we could have chatted sometime in the future over a cup of tea about how tough it was now. I have lost a comrade and am consumed with sorrow.

Keiko Sakurai, professor of Gakushuin University Faculty of Law

“Recalling Akihiro Sawa”

I had been thinking that I hadn’t heard from Akihiro Sawa recently, and I am numb at this news. It is a terrible loss of such a promising person, so thoroughly knowledgeable was he about energy policy. Sawa—whom I knew as a person of great presence, great energy, rushing from place to place, listening to people everywhere, and making positive political proposals—was a man with a firm sense of mission.

It was after the nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi NPPs in 2011 that I started working with him. Japan’s nuclear policy had experienced a major setback, and nuclear operators, academicians, politicians and administrators were all trying to complete a “zero-base” review of the state of things to that point, struggling to produce a new vision. That was when I went to talk with Sawa.

My concerns were many: (1) the organizational theory underlying the Nuclear Regulation Authority, (2) a proposal to revise the Reactor Regulation Law, (3) administrative procedures for nuclear operators, (4) the legal positioning of regional residents and local governments, (5) the weaknesses of the nuclear emergency response system, (6) the problems of a nuclear damage compensation system, and (7) how to respond to judicial judgments in individual cases. Sawa was interested in all the questions I raised, and always tried to incorporate what he thought was good into his political proposals—that was our pattern. Certainly busy with his own lectures and presentations, he took the time to listen to me on a legal case involving NPPs. I recall him saying, as he typed on his computer, “I will go to sleep only if you tell me something I’ve heard before.”

I participated several times in symposia coordinated by Sawa. More than once did I check with him in advance on whether something I wanted to say might seem too harsh to the nuclear industry. Each time he encouraged me, “No, no. I want those in the ‘nuclear village’ to broaden their outlook. Say it just like it is.” There was something inspiring to others in his enthusiasm to restore the nuclear industry in the appropriate manner. He was attempting to introduce a social science point of view to an industry focused on technical thinking, and I believe that he was aware of his role as a “node.”

Nuclear policy in Japan has just experienced a major shift, and full implementation now lies ahead. I am sure Sawa would regret not being here to see the picture he helped to paint. May he rest in peace.