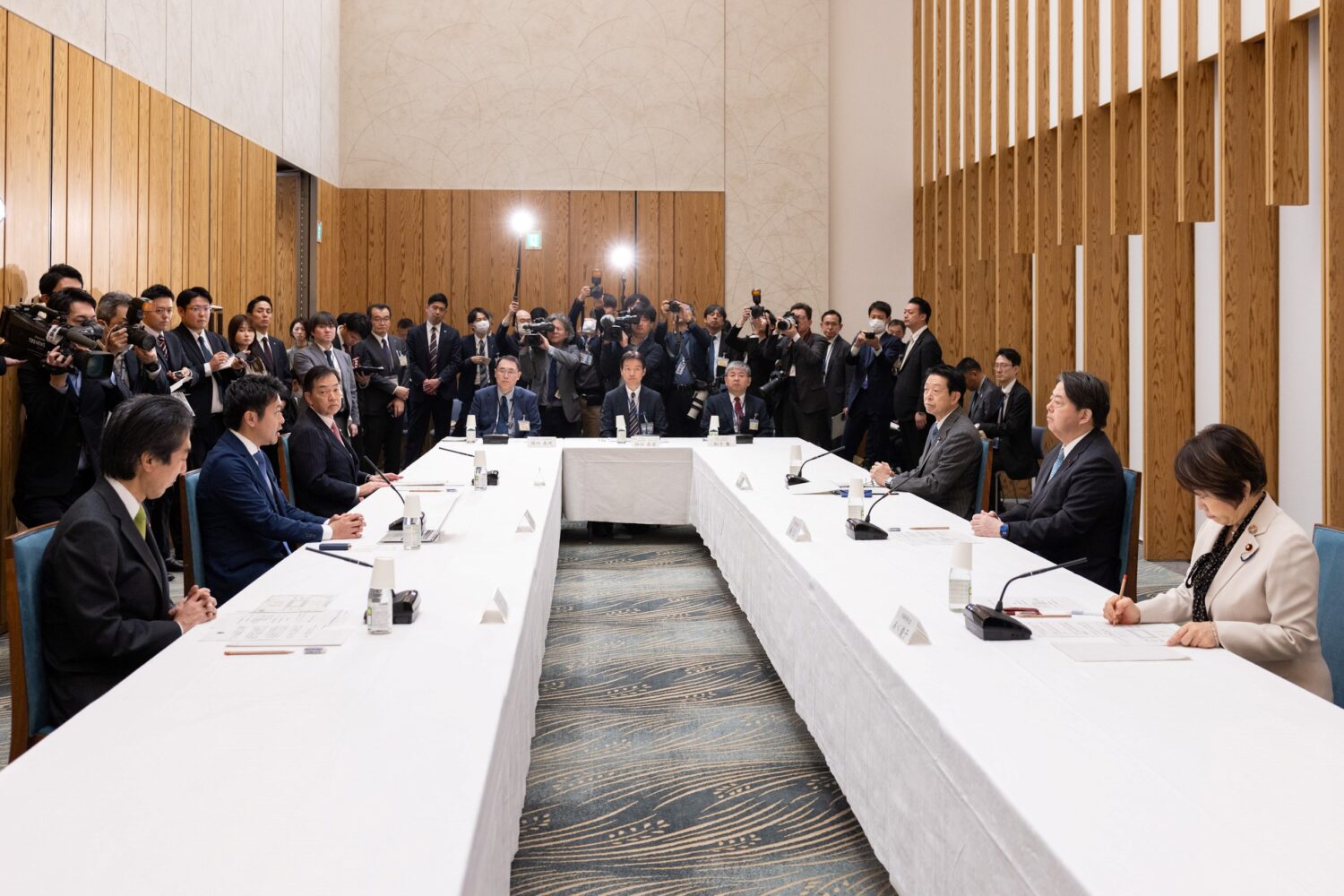

At the start of the meeting, Minister Hiroshi Kajiyama, head of Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) said, “Given Japan’s goal of carbon neutrality by 2050, along with the new target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 46% from 2013 levels by the year 2030, efforts are very important in the energy field, in which greenhouse gas emissions account for more than 80% of total emissions.” He asked the policy committee to deepen its deliberations based on the draft.

From the dual perspectives of responding to climate change and overcoming issues in Japan’s energy supply-and-demand structure, the draft of the new Strategic Energy Plan primarily focuses on three areas:

- The decade since the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi.

- Issues and actions toward realizing carbon neutrality by 2050.

- Political measures by 2030, looking toward 2050.

Prior to detailed explanations, it was clearly stated at the meeting that in March 2021, in recognition of the decade that has passed since the Great East Japan Earthquake and the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi in March 2021, “resetting Japan’s energy policy is the starting point in revising the Strategic Energy Plan, keeping the experiences, regrets and lessons learned from the Fukushima Daiichi accident uppermost in mind.”

Toward the achievement of carbon neutrality by 2050-the goal declared by Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga last fall-the draft refers to five specific endeavors:

- Discussing issues and carrying out actions toward realizing carbon neutrality by 2050.

- Developing political measures by 2030, looking toward 2050.

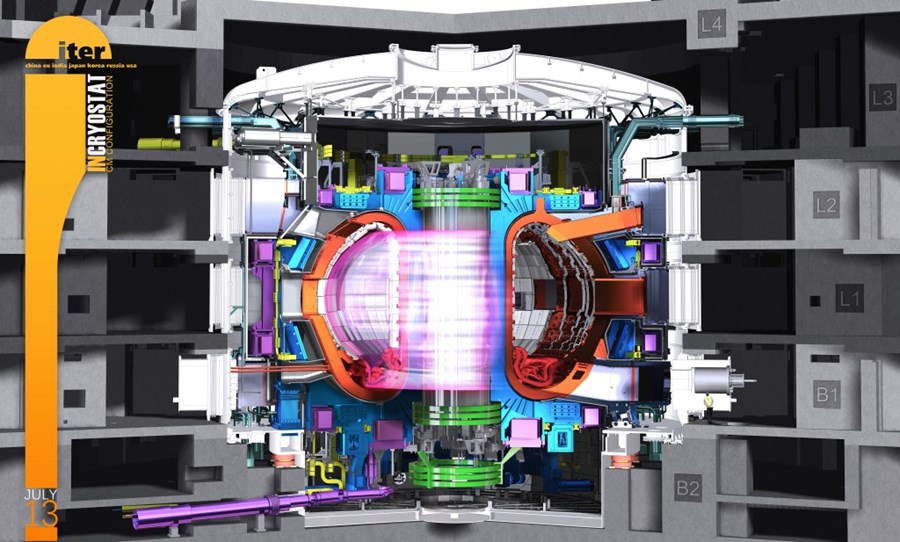

- Striving to utilize low-carbon power sources that are at practical stages of development, including renewable energies and nuclear power.

- Pursuing innovation in thermal generation, including hydrogen/ammonia and carbon-dioxide capture, utilization and storage (CCUS).

- Shifting to the use of low-carbon electricity in the industrial, household, and transport sectors.

Meanwhile, regarding nuclear power, several phrases used in the current plan (in the context of a 2050 scenario) will remain. Namely, dependency on nuclear power will be reduced as much as possible while renewable energies become more broadly used in society. The construction of new reactors and of replacements for older ones is not specifically mentioned, although the “necessary scale will be utilized sustainably.”

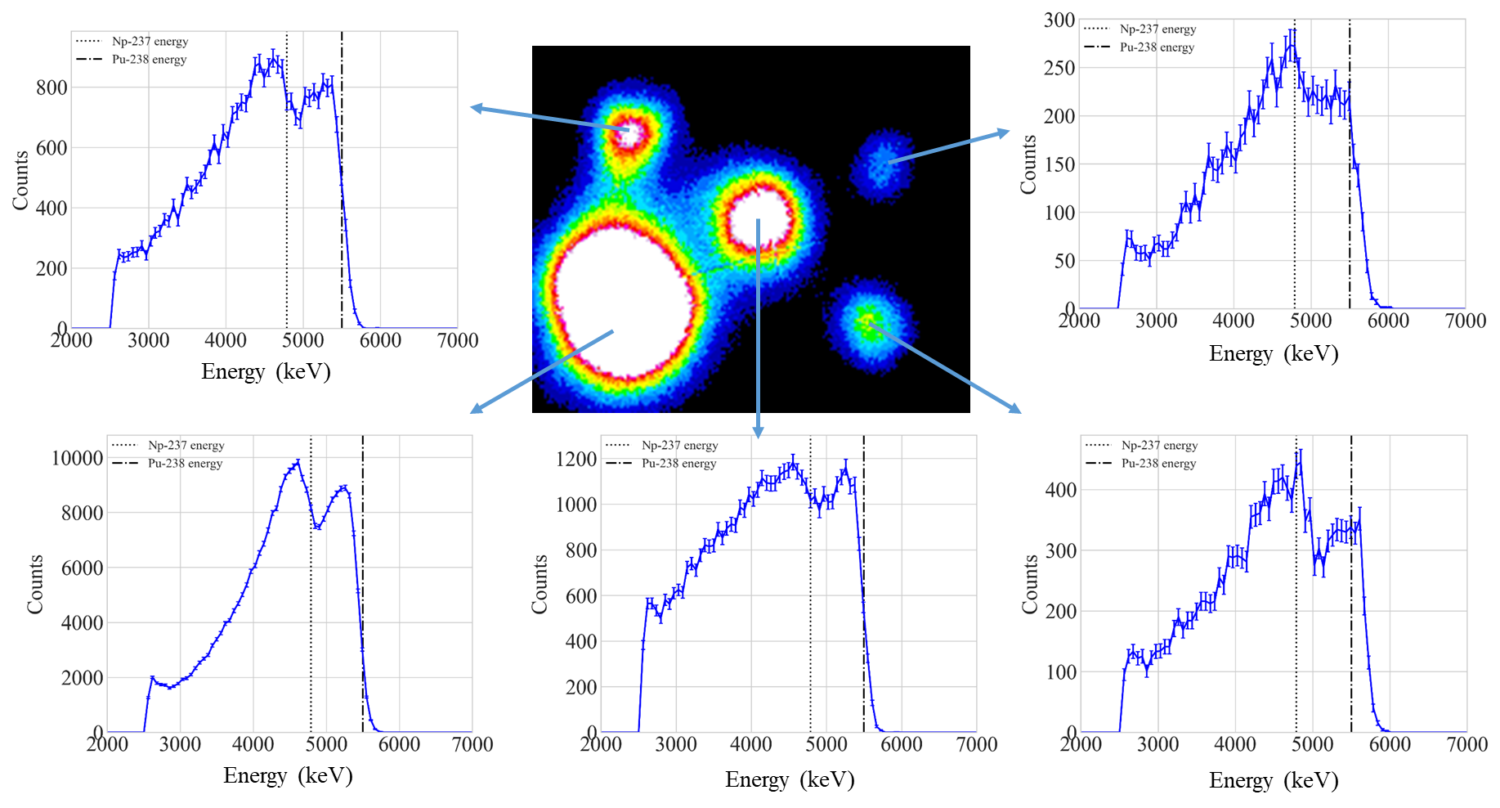

The draft also cites the following: (1) reinforcing nuclear human resources, technologies and industrial infrastructure, (2) developing reactors that excel in terms of safety, economy and flexibility/mobility, and (3) developing technological solutions for back-end issues.

Along with global trends toward decarbonization, the draft refers to various changes in the global situation since 2018, when the current (fifth) Strategic Energy Plan was issued. The risks include: (1) threats to the stability of energy supplies, including changes in lifestyles due to continuing spread of COVID-19, (2) increasing tensions in global security as a result of increased Sino-U.S. friction, (3) the greater frequency of natural disasters, and (4) cyberattacks. The draft clearly states that “actions based on those internal and external changes are required in the current era.”

In terms of political measures to be taken toward 2030, the basic policy is to maximize efforts to realize Japan’s goal of “S+3E” (the conventional three E’s of energy security, economic efficiency, and environmental protection, plus safety). They comprise thorough energy conservation on the demand side, and efforts to ensure energy sources and natural resources and fuel in stable manner on the supply side.

The draft also states that measures for nuclear power “will be steadily carried out without postponement.” Those include:

- Restarting nuclear reactors, with safety as the top priority.

- Promoting spent fuel measures.

- Promoting the nuclear fuel cycle.

- Carrying out investigations toward the selection of a final disposal site for high-level radioactive waste (HLW).

- Working on various issues involving long-life reactor operation.

- Improving public understanding (including that of residents in power-consuming areas).

The draft also refers to establishing relationships of trust with people nationally, along with those in NPP siting regions and the international community at large. It also cites the promotion of research and development.

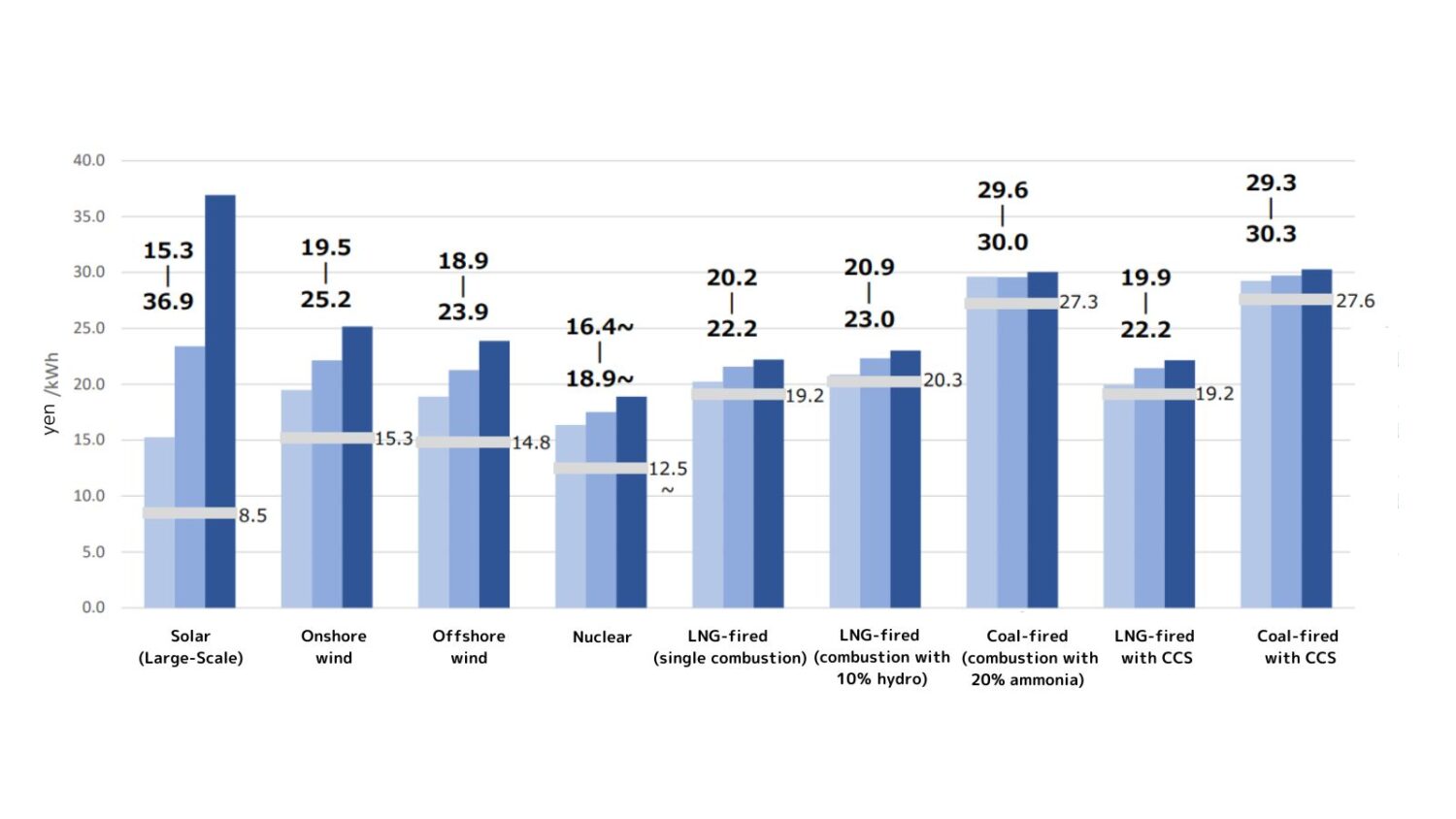

The draft goes on to graphically illustrate an energy supply and demand outlook for 2030, on the assumption that “issues are ambitiously overcome both on the demand and supply sides.” The total generated electricity in 2030 is expected to be 930TWh, about 13% below the 1,065TWh projected in the current projected energy mix.

The new power-source composition would be 36-38% for renewable energies (up from 22-24% in the current projected mix), 1% for hydrogen/ammonia (up from 0%), 20-22% for nuclear power (unchanged), 20% for LNG (down from 27%); 19% for coal (down from 26%), and 2% for oil (down from 3%).

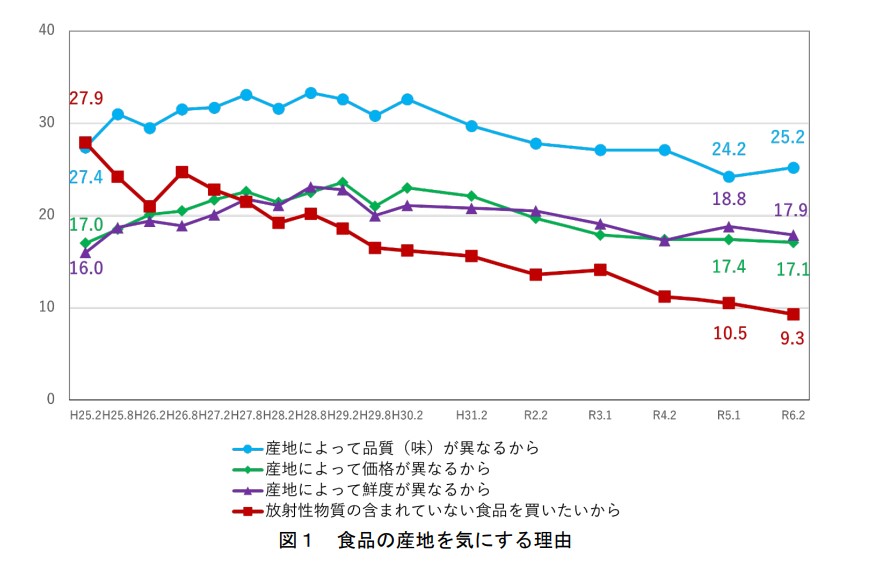

Concrete descriptions of energy education are presented in a section of the draft dealing with enhancing communications with all sectors of the public, with the Atomic Energy Society of Japan (AESJ) having recently released the results of its investigation of descriptions of energy subjects in junior-high textbooks.

The draft states, “Questions of choices of energy arise in various subjects in academic curricula, including science, social science, home economics, and technology.” Given that there are no ‘correct’ answers, and that students deepen their own thinking and come to recognize the theme as a matter of personal importance, it emphasizes the significance of education.

It then gives examples of how to develop lessons on energy and supplemental materials, how to create game content to provoke thinking about balance in electric power, and how to support teachers engaged in energy education nationwide.

The Strategic Policy Committee will continue its deliberations based on discussions at the July 21 meeting, toward formulating the next Strategic Energy Plan.

-1.png)

.jpg)